Weight loss is one of the most common symptoms of cancer. It often happens because cancer treatment can lower people’s appetites. Sometimes, though, people can lose weight even when their diet doesn’t change.

This could be cachexia.

Cachexia is a condition that involves extreme loss of muscle and fat. It can look like a person is wasting away from the drastic weight loss, hence its nickname, wasting syndrome.

“We generally see a wasting of body tissue, particularly muscle. And that may impact the way people feel,” says Dr Clare Shaw, a leading cancer dietician at the Royal Marsden Hospital.

“We also see that people will lose body fat, so they might lose weight a little bit faster than they would expect on the food intake that they’re having.”

But cachexia is more than weight loss. It’s a complex problem that can affect up to 8 out of 10 people with advanced cancer, depending on their tumour type.

The effects of cachexia

At its worst, the syndrome can cause severe physical deterioration. This can have major impacts on a person’s life, leaving them feeling so fatigued and weak that everyday activities like going for a walk or taking a bath can become incredibly difficult.

At times, lying in bed can feel like running a marathon.

Cachexia can also impact someone’s ability to go through cancer treatment. It can cut lives short too.

It’s one of the most pressing issues in cancer research and cancer care.

That’s why we’re tackling it through Cancer Grand Challenges, the global funding initiative we co-founded with the National Cancer Institute in the US.

Using data from our flagship lung cancer study TRACERx, the Cancer Grand Challenges team CANCAN has found a marker called GDF15, which could help to predict who’s at risk of developing cancer-associated cachexia.

The team found a strong correlation between cachexia and levels of the blood protein GDF15, which other studies have previously linked with appetite and weight loss. Testing for it could help doctors treat the syndrome before it becomes too debilitating.

Defining cachexia

Previously there were many different criteria for identifying cachexia. But in 2011, an international consensus group adopted a definition to make its differences from weight loss clearer.

Essentially it means that, while in weight loss generally we see a loss of fat that eating can reverse, cachexia has an extreme loss of muscle (along with fat) that diet alone cannot solve.

Cancer isn’t the only cause of cachexia. People with other illnesses such as heart disease, HIV and kidney disease can also develop it. This article is specifically about cancer-associated cachexia.

There are 3 clinical stages: pre-cachexia, cachexia and refractory cachexia. In pre-cachexia people experience a few symptoms but their body weight is generally stable. Cachexia is defined as weight loss greater than 5% of body weight. And in refractory cachexia, maintaining a fixed body weight is no longer possible and people experience severe wasting. Not everyone with cachexia will experience all stages but it helps categorise the level of management for clinicians.

The likelihood of developing cachexia varies by tumour type. For example, over 80% of people with stomach or pancreatic cancer develop some form of cachexia, compared to around 40% of people with breast cancer and leukaemia.

Metabolic disturbances

But what causes cachexia?

Well, researchers believe that inflammation from cancer could drive it.

Inflammation happens as cancer cells try to bring in more nutrients and oxygen. They release chemical signals to lure immune cells, like macrophages and granulocytes, to infiltrate the tumour.

Once inside the tumour, these immune cells secrete inflammatory molecules called cytokines. Cytokines encourage new blood vessels to grow and bring in nutrients and oxygen that the tumour needs to grow and survive, in a process called angiogenesis.

In effect, the tumour uses these blood vessels to redirect nutrients from the food we eat to meet its own energy needs.

Meanwhile, inflammation is also linked directly to muscle loss. It causes protein to be broken down faster than it’s being made.

In the cells of the muscle, structures called mitochondria are responsible for converting nutrients to energy (also called metabolism) and are critical in maintaining muscle. But cancer can damage the mitochondria, so the energy they usually store becomes used up and changes the metabolism.

Burning through fat

One hallmark of cachexia is that it can cause people to lose fat at an alarming rate.

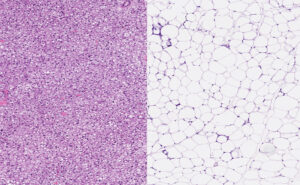

Brown fat cells (left) and white fat cells (right) under a microscope. vetpathologist/Shutterstock.com

There are two types of fats in the body – brown and white. We have more white fat and it’s what we tend to associate with the word fat. It stores energy as large fat droplets inside cells called adipocytes – energy reserves for when we need them.

However, brown fat uses energy by creating heat to maintain our body temperature. Brown fat in adults is mainly in the neck and shoulders (making up 5-10% of total fat tissue). It’s activated by cold temperatures and chemical signals in the body.

Cytokines can change how our fat cells work. They turn from white, energy-storing cells to brown or beige cells that burn energy to create heat. This process is called browning. The body is then burning through more energy than usual.

Sometimes, people can’t eat enough food to compensate for their bodies burning through muscle and energy reserves.

That’s made much worse by the fact that proteins like GDF15 can impact appetite, and the way tumours siphon nutrients from the rest of the body.

How does cachexia change appetite?

We’re learning that bodily and behavioural changes can affect weight loss in cachexia.

- The brain

Inflammatory cytokines released from tumours can infiltrate the brain, where they interfere with the levels of hormones responsible for appetite. It causes people with cachexia to not feel hungry despite burning through so much energy.

- The gut

Researchers also believe inflammation from cachexia could lead to changes in the gut microbiome, a community of trillions of bacteria, yeast and other microbes that, among many other things, support our health and help us digest food. Early studies suggest that changes in the microbiome’s composition are associated with cachexia and could be a possible target for therapy.

Can cachexia be managed with diet?

Currently there are no globally approved therapies or treatments for cachexia. But researchers are looking for ways to manage symptoms and stop it progressing.

A big difference between cachexia and diet-related weight loss is that nutritional intervention alone cannot reverse the full effect of cachexia. But that doesn’t mean it can’t help.

So adding more calorific foods and meal supplements, such as peanut butter and prescribed shakes, can help prevent extensive fat loss. That’s true even if the amount of food eaten is still quite low. Researchers believe that increasing fatty foods rich in omega 3 (like oily fish) could help reduce inflammation in people with cachexia. Early studies in animals showed positive results, but this idea hasn’t been fully explored in humans yet.

The main target for reducing cachexia symptoms is maintaining muscle. Muscle is made of different amino acids, so researchers are also looking at amino acid supplementation. In fact, many people with cachexia are deficient in carnitine, a nutrient derived from an amino acid that can be purchased at any sports health shop. 95% of carnitine is stored in skeletal muscle and it’s responsible for delaying fatigue during exercise.

Studies show that carnitine supplementation can help to stop muscles breaking down. But research has also shown that too much carnitine can cause serious side effects like high blood pressure, so it must be carefully monitored.

Researchers have also tested other amino acid supplements, but at this stage they do not appear to improve cachexia symptoms. One theory is that the metabolic changes caused by cachexia could be influencing the uptake of supplements, minimising their positive effects.

However, interventions that combine multiple nutrients, like amino acids and fatty acids, appear to work better than single supplements. One study found that a combination of the amino acids leucine, arginine and methionine with unsaturated fatty acids almost doubled the rate mice build muscle.

Anti-cachexia drugs?

Researchers are also focussing on targeted approaches using different drugs to help tackle cachexia.

- Boosting appetite

Improving appetite could help keep up with the high levels of energy burned during cachexia. A drug called anamorelin mimics the hunger hormone, ghrelin. Ghrelin is made by the stomach lining and regulates appetite by creating sensations of hunger.

Two large trials, ROMANA 1 and 2, showed promising results from giving anamorelin to people with cachexia. They could tolerate the drug and it helped manage symptoms by increasing both muscle mass and overall weight.

- Tackling inflammation

A more obvious target is the root of the problem – inflammation. Anti-inflammatory drugs can block the cytokines responsible for cachexia. But research into anti-inflammatory drugs for cachexia is still in its early stages.

One of these early stage trials, called MENAC, is looking at a combination of treatments for cachexia. This includes a monitored high calorie diet, supplements, exercise and using anti-inflammatory drugs. The trial is complete and we’re awaiting the results.

Getting closer with CANCAN

What we’re really hoping for is precise targeting, a way to efficiently stop the problem at its core. And it may be closer than we think.

CANCAN has found distinct gene activity was much more likely in the tumours of people with cachexia. This could lead to a way to diagnose the condition before symptoms appear. It’s a huge step forward because one of the hardest things about cachexia is to recognise it’s happening before it becomes debilitating.

TRACERx recognises that cancer is not static and the way we treat patients shouldn’t be either. This approach that we’ve been able to take – following patients through their cancer journey and looking at how cancer interacts with the whole body – has allowed us to interrogate this condition in a way that hasn’t been possible before.

Professor Charles Swanton, Cancer Research UK Chief Clinician and TRACERx Lead.

The researchers used a cutting-edge AI-assisted method to process hundreds of scans from people with lung cancer. From the scans they were able to track their abdominal fat and muscle. This meant that they could identify patients with cachexia and compare people with and without the condition in unprecedented detail.

“The incredible investment and in-depth sample and data collection in TRACERx has allowed us to begin to make discoveries in cachexia,” says Dr Mariam Jamal-Hanjani, the lead researcher on CANCAN.

“We’re particularly excited about trying to find alterations in the cancer or blood that can help identify which patients are at risk of developing cachexia in the future so that we can intervene before this happens.”

From diagnosis to treatment, cachexia’s complexity has puzzled researchers for a long time. And we’re following closely as CANCAN continues its mission to understand cachexia.

Already there’s so much progress being made in unravelling cachexia’s mysteries. Increasingly, we have reason to hope that one day this complex syndrome might be treatable.

The post Wasting syndrome: What is cachexia? appeared first on Cancer Research UK – Cancer News.